Demystifying Pricing in the Voluntary Carbon Market

Demystifying Pricing in the Voluntary Carbon Market

Demystifying Pricing in the Voluntary Carbon Market

KNOWLEDGE & INSIGHTS

September 11, 2023

Grace Lam

·

Co-founder

Mar Velasco

·

Co-founder

The voluntary carbon market (VCM), as with any marketplace, has buyers and sellers who agree on a common price for credits. It is designed for the private sector where corporates (the buyer) can purchase carbon credits either directly from project developers (the seller) or indirectly on marketplace platforms. This can help them reduce their net emissions and even potentially remove CO2 from the atmosphere, outside of the purview of their own supply chains. This is in contrast to compliance carbon markets – typically a cap-and-trade system where government entities mandate and regulate carbon trading activities – which facilitate trading on carbon emission allowance between firms.

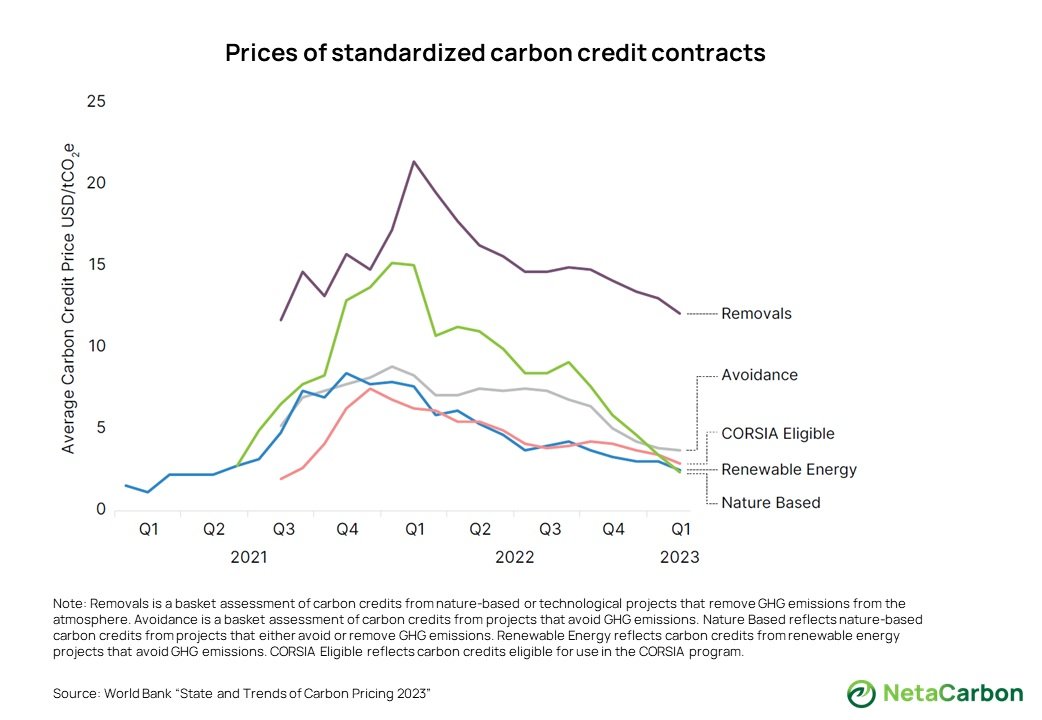

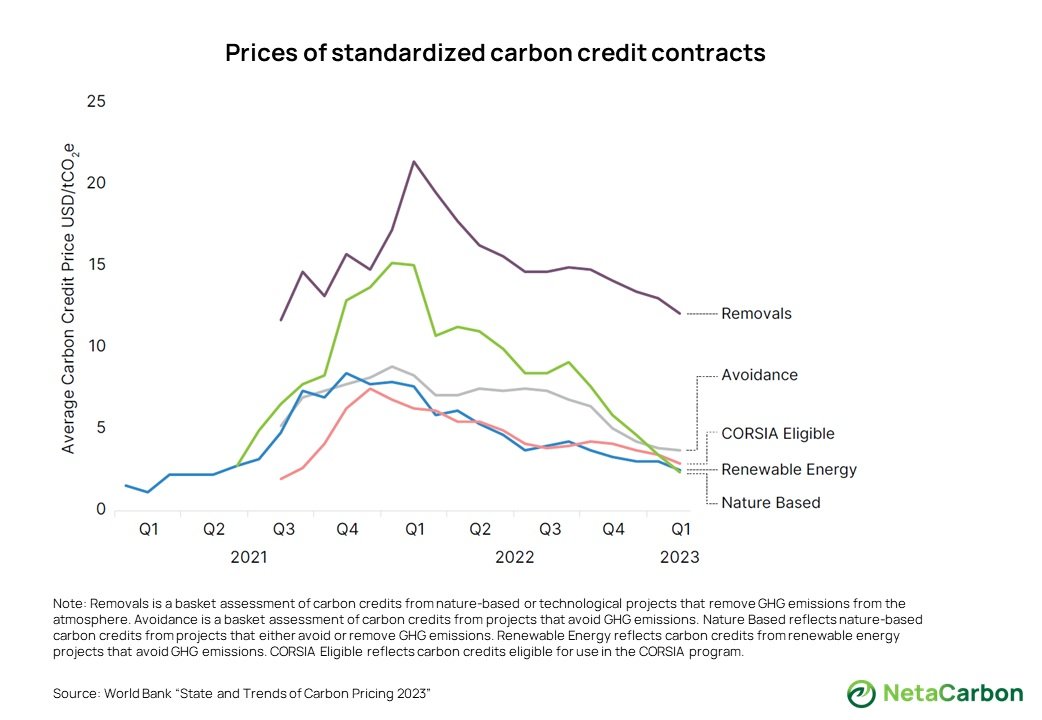

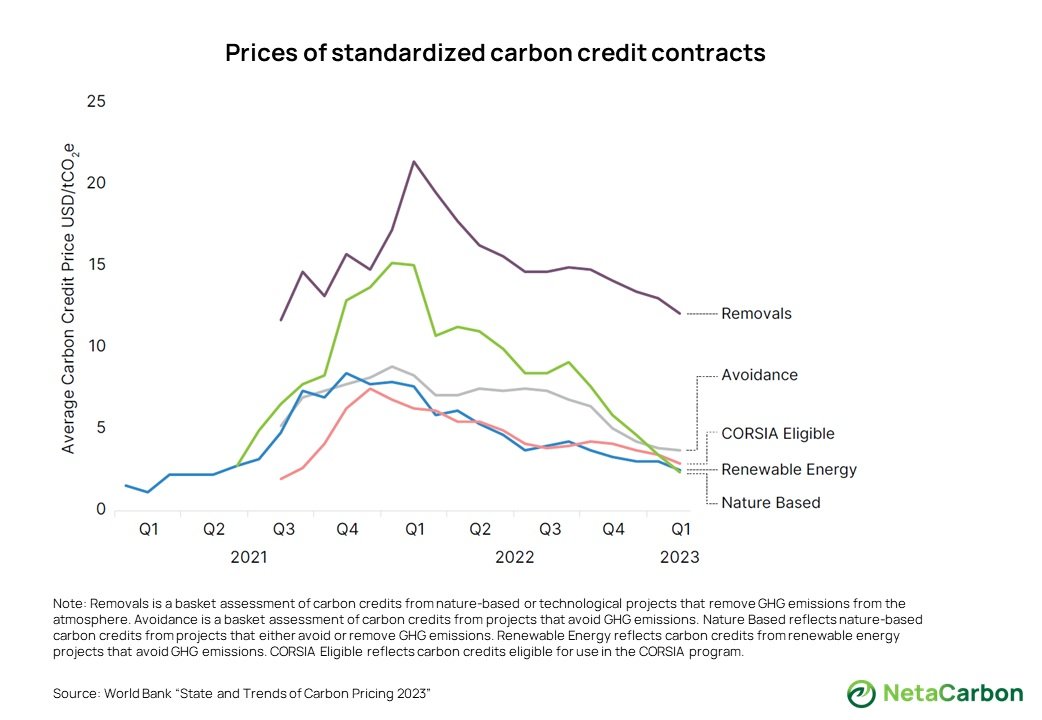

Since 2000, 1,800 million metric tonnes of carbon credits have been issued across the four main registries (Verra, Gold Standard, CAR, ACR), as of Q1 2023. In 2022 alone, 146 million metric tonnes of CO2 were retired on the VCM, according to data from the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project. However, there is significant variation in pricing based on project methodology as seen through World Bank’s tracking, based on data from S&P Global:

Exhibit 1: Pricing of carbon credits by project type, according to pricing data tracked by S&P Global.

As such, much of carbon credit pricing remains opaque and difficult to grasp, especially for newcomers to the market – why is one tonne of CO2 valued differently across projects?

Some commentators take a “commodity” approach, arguing that there should be a uniform price across all carbon credits, just like most other traded commodities. However, similar to many climate practitioners, we see the necessity of varied carbon credit prices. In this blog post, we demystify why carbon prices vary due to three major factors, which illustrate why we still believe they should continue to vary.

Factor 1: Project Types & Methodologies

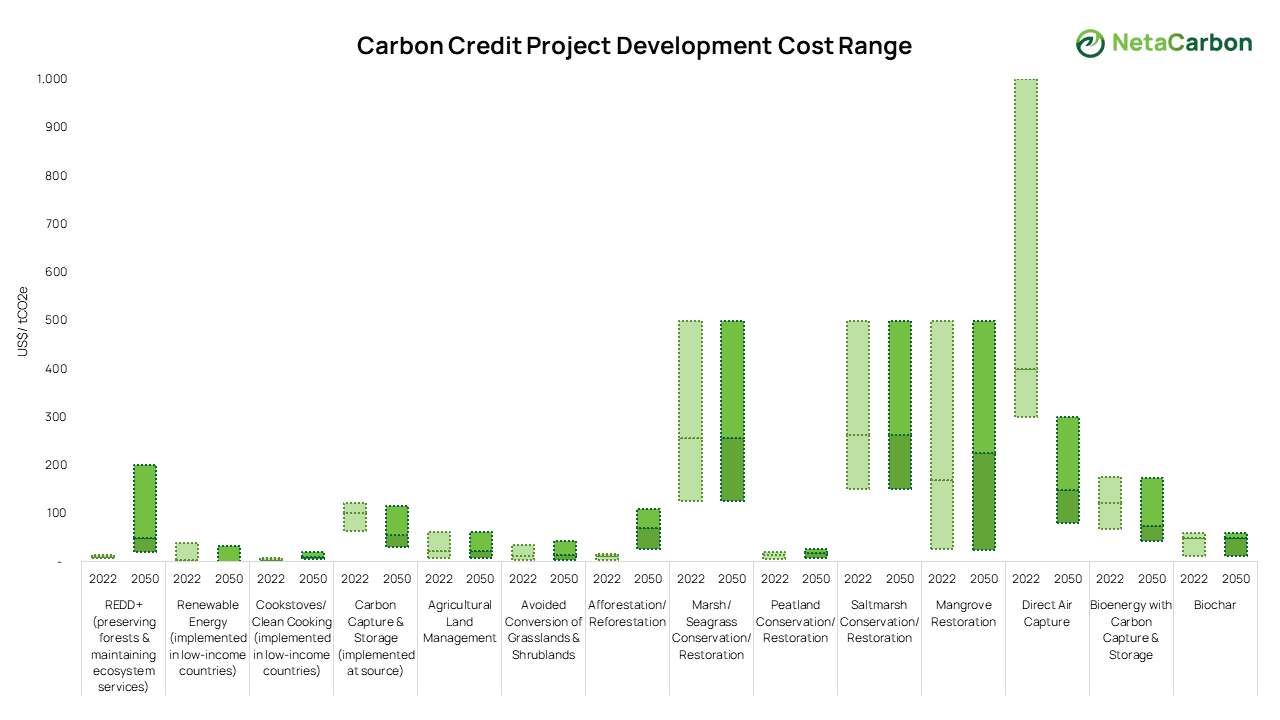

The number one determining factor for carbon credit pricing is the project type – whether it is a carbon removal or reduction/avoidance credit, and whether it is a nature-based or engineered removal credit. The project type has an implication on the cost of project development and any other potential revenue streams for the project outside of the financing received from carbon credits. As a rule of thumb, removal credits, which often rely on engineering interventions, tend to be more expensive than reduction credits due to higher technological costs and limited alternate revenue streams.

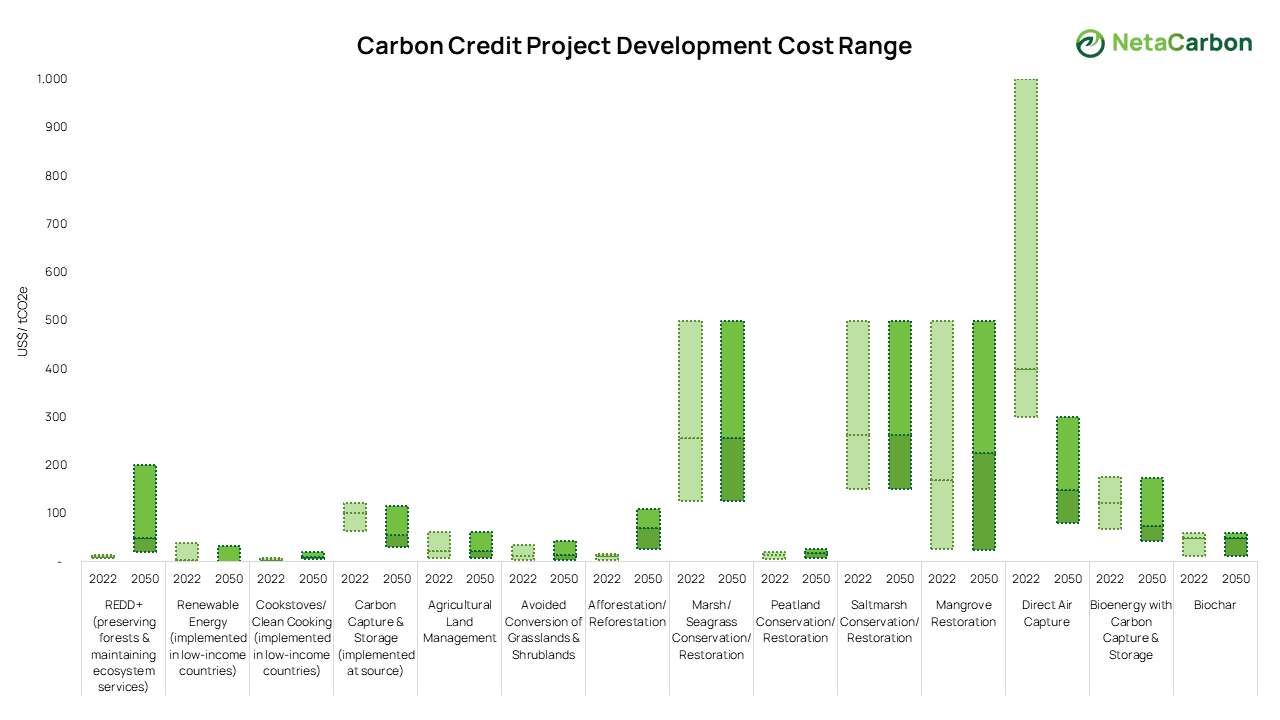

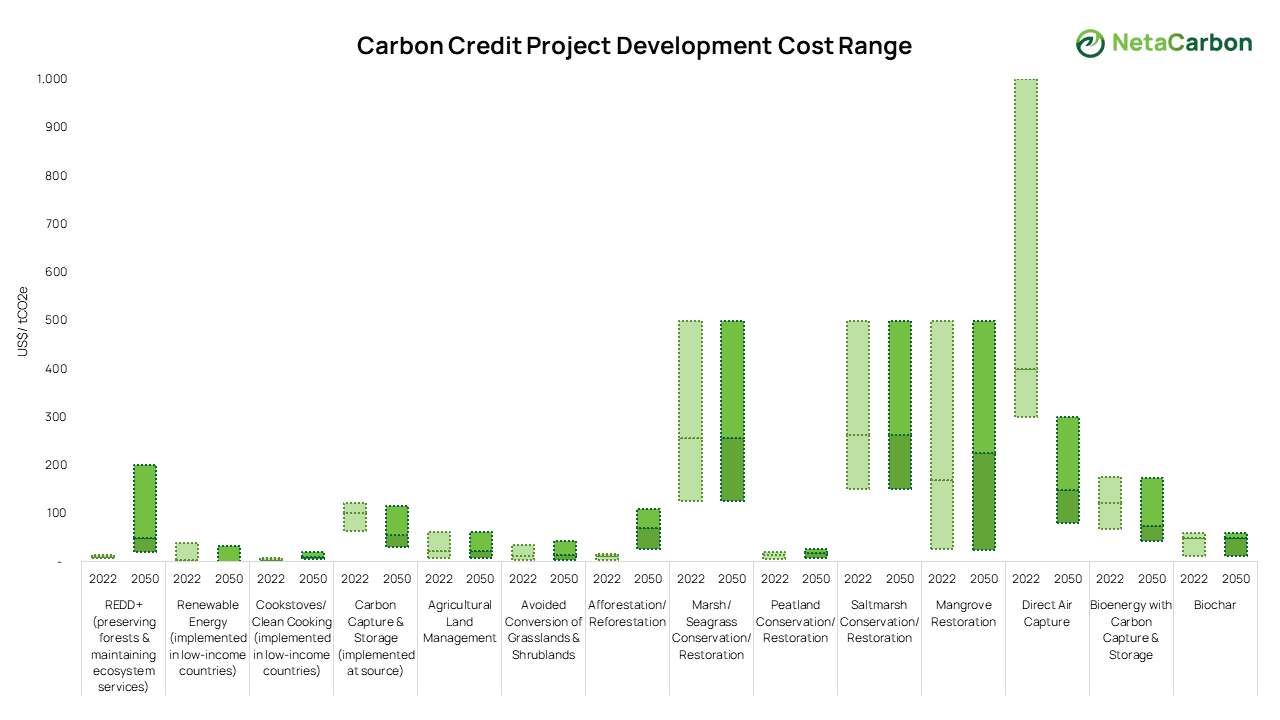

Trove Research, a research firm specializing in VCM-related data, explains the cost ranges of the most common types of projects and how they are predicted to evolve, which we summarized in the chart below. Note that a project developer would need to factor in additional costs related to verifying and issuing a carbon project and their margin to determine the ultimate selling price of each unit of carbon credit.

Exhibit 2: Cost ranges by major categories of carbon credits.

Their research demonstrates that project development costs can vary considerably, which in turn would result in a divergence in pricing across carbon projects. Based on these supply-side constraints, we cannot assume a blanket price simply because each project technically represents one unit of carbon dioxide reduction or removal.

Their work also shows that the cost of carbon removal technologies will fall with time due to ongoing innovation spurred across countries through compliance mandates and/or market incentives, like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the United States. The resulting economies of scale and learning effects will further create new technological solutions not yet viable today. Nevertheless, the average price of carbon credits is still expected to increase due to increasing pressure on productive land use, global and local economic growth, and improvements in credit quality and measurement technology which will improve the quality of carbon credits available on the VCM.

Factor 2: Quality and Co-Benefits

The quality of a carbon credit is another key factor determining its market price. A high-quality carbon credit adheres to ICVCM's ten core principles, as we discussed in an earlier blog post. Strong supporting evidence on additionality, permanence, and absence of leakage legitimizes and justifies a higher credit price. Conversely, the uncertainty on credit quality alone could tumble prices. REDD+ projects, which became the center of controversy due to suspected over-crediting claims, have seen their value halved from that of last year.

Associating strong co-benefits with the project also helps boost credit prices. Credits that demonstrate co-benefits like improving livelihoods, creating local jobs, and empowering women, taking on a more comprehensive understanding of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, have historically received 30.4% higher market prices.

However, co-benefits are much harder to quantify than the costs of a carbon credit project as they are either intangible or non-monetary (like improved community health). Moreover, available forms of measurement currently lack global metric standardization and disclosure principles.

But there’s hope! We are already seeing rapid development of new technology for robust verification, and quantification mechanisms that take all stakeholders into account and will help instill buyer confidence in the VCM. This is a testament to the increasing diversity of people coming together to fight climate change.

Consequently, project developers should strive to incorporate and quantify co-benefits toward local communities into their projects, ideally going above and beyond what is required by the verifiers. Our experience is that the better a project can quantify and display its co-benefits (with transparency and proofs), the more attractive the project will be to buyers, boosting the transaction prices higher than projects that display limited co-benefits.

Factor 3: Spot Pricing vs. Forward Contracts

A buyer can either pay a spot price (i.e., a price for immediate purchase and delivery of carbon credits from active projects) or commit to a forward contract, which locks in an agreed-upon price for delivery of the carbon credit at a future date. By locking in a fixed future price, forwards provide buyers with a financial instrument to reduce their risk exposure given fluctuating market prices; in turn, they provide project developers with pre-financing funds to implement the carbon projects.

Data on carbon project forwards is typically not publicly available, as they are bespoke contracts between buyers and sellers (i.e., project developers). Through speaking with project developers, we typically see that forward prices are discounted, reflecting the project risks buyers absorb by providing upfront financing. Meanwhile, the nascency of the spot carbon market could give rise to pricing volatility due to temporary market shocks.

We expect that forward contracts will become increasingly popular as supply becomes limited and buyers demand more visibility and transparency throughout the entire carbon project development cycle. Most importantly, they provide project developers with critical market signals and access to private finance as they develop long-term carbon reduction and removal projects with high costs now for credit delivery and payments in the future.

But…is any of this pricing fair?

Our standard macroeconomic models often fail to explain the many unintended costs and benefits of a transaction on third parties. Just as the co-benefits of carbon credit projects are hard to measure, it is equally hard to determine the fair price to pay for an activity that reduces or removes one metric tonne of CO2. One way to understand this concept of “fair pricing” is through the social cost of carbon, which is the theoretical estimate of the cost of damage to society done by each additional tonne of carbon emissions (or, on the flip side, the benefit of reducing or removing one metric tonne of CO2).

The Obama and Biden administrations have led rigorous exercises into determining the social cost of carbon to guide policy decisions, setting it between US$ 43–51 per metric tonne of CO2e, while the EPA has proposed raising it to US$ 190. These figures are notably higher than the prices we see in the voluntary carbon market, which begs the question: are the current prices in the voluntary market sustainable and fair, given the social benefits it could bring through reducing or removing carbon emissions?

From these perspectives, it is clear that carbon credits on the VCM are currently trading at steep discounts due to a lack of standardization and institutional gaps, coupled with a lack of consensus around the true cost of emitting carbon. There is also a real need for varied pricing to differentiate between crediting methodologies and project specifics.Recognizing this, NetaCarbon’s primary focus is to build systematic approaches and methodologies to support suppliers in gaining easier access to the VCM. We can help them by streamlining regulation navigation, the verification and quality certification process, and project management. In doing so, we aim to close the supply gap of carbon projects and reduce the overall climate cost to our planet and globally underserved communities. If you are interested in developing a carbon project, please reach out to us!

We would like to thank Amrita Roy for her contribution to this blog post and Rehan Mirza for editorial support. For this blog post, we drew upon data from the World Bank, Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, Trove Research, and S&P Global Platts.

The voluntary carbon market (VCM), as with any marketplace, has buyers and sellers who agree on a common price for credits. It is designed for the private sector where corporates (the buyer) can purchase carbon credits either directly from project developers (the seller) or indirectly on marketplace platforms. This can help them reduce their net emissions and even potentially remove CO2 from the atmosphere, outside of the purview of their own supply chains. This is in contrast to compliance carbon markets – typically a cap-and-trade system where government entities mandate and regulate carbon trading activities – which facilitate trading on carbon emission allowance between firms.

Since 2000, 1,800 million metric tonnes of carbon credits have been issued across the four main registries (Verra, Gold Standard, CAR, ACR), as of Q1 2023. In 2022 alone, 146 million metric tonnes of CO2 were retired on the VCM, according to data from the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project. However, there is significant variation in pricing based on project methodology as seen through World Bank’s tracking, based on data from S&P Global:

Exhibit 1: Pricing of carbon credits by project type, according to pricing data tracked by S&P Global.

As such, much of carbon credit pricing remains opaque and difficult to grasp, especially for newcomers to the market – why is one tonne of CO2 valued differently across projects?

Some commentators take a “commodity” approach, arguing that there should be a uniform price across all carbon credits, just like most other traded commodities. However, similar to many climate practitioners, we see the necessity of varied carbon credit prices. In this blog post, we demystify why carbon prices vary due to three major factors, which illustrate why we still believe they should continue to vary.

Factor 1: Project Types & Methodologies

The number one determining factor for carbon credit pricing is the project type – whether it is a carbon removal or reduction/avoidance credit, and whether it is a nature-based or engineered removal credit. The project type has an implication on the cost of project development and any other potential revenue streams for the project outside of the financing received from carbon credits. As a rule of thumb, removal credits, which often rely on engineering interventions, tend to be more expensive than reduction credits due to higher technological costs and limited alternate revenue streams.

Trove Research, a research firm specializing in VCM-related data, explains the cost ranges of the most common types of projects and how they are predicted to evolve, which we summarized in the chart below. Note that a project developer would need to factor in additional costs related to verifying and issuing a carbon project and their margin to determine the ultimate selling price of each unit of carbon credit.

Exhibit 2: Cost ranges by major categories of carbon credits.

Their research demonstrates that project development costs can vary considerably, which in turn would result in a divergence in pricing across carbon projects. Based on these supply-side constraints, we cannot assume a blanket price simply because each project technically represents one unit of carbon dioxide reduction or removal.

Their work also shows that the cost of carbon removal technologies will fall with time due to ongoing innovation spurred across countries through compliance mandates and/or market incentives, like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the United States. The resulting economies of scale and learning effects will further create new technological solutions not yet viable today. Nevertheless, the average price of carbon credits is still expected to increase due to increasing pressure on productive land use, global and local economic growth, and improvements in credit quality and measurement technology which will improve the quality of carbon credits available on the VCM.

Factor 2: Quality and Co-Benefits

The quality of a carbon credit is another key factor determining its market price. A high-quality carbon credit adheres to ICVCM's ten core principles, as we discussed in an earlier blog post. Strong supporting evidence on additionality, permanence, and absence of leakage legitimizes and justifies a higher credit price. Conversely, the uncertainty on credit quality alone could tumble prices. REDD+ projects, which became the center of controversy due to suspected over-crediting claims, have seen their value halved from that of last year.

Associating strong co-benefits with the project also helps boost credit prices. Credits that demonstrate co-benefits like improving livelihoods, creating local jobs, and empowering women, taking on a more comprehensive understanding of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, have historically received 30.4% higher market prices.

However, co-benefits are much harder to quantify than the costs of a carbon credit project as they are either intangible or non-monetary (like improved community health). Moreover, available forms of measurement currently lack global metric standardization and disclosure principles.

But there’s hope! We are already seeing rapid development of new technology for robust verification, and quantification mechanisms that take all stakeholders into account and will help instill buyer confidence in the VCM. This is a testament to the increasing diversity of people coming together to fight climate change.

Consequently, project developers should strive to incorporate and quantify co-benefits toward local communities into their projects, ideally going above and beyond what is required by the verifiers. Our experience is that the better a project can quantify and display its co-benefits (with transparency and proofs), the more attractive the project will be to buyers, boosting the transaction prices higher than projects that display limited co-benefits.

Factor 3: Spot Pricing vs. Forward Contracts

A buyer can either pay a spot price (i.e., a price for immediate purchase and delivery of carbon credits from active projects) or commit to a forward contract, which locks in an agreed-upon price for delivery of the carbon credit at a future date. By locking in a fixed future price, forwards provide buyers with a financial instrument to reduce their risk exposure given fluctuating market prices; in turn, they provide project developers with pre-financing funds to implement the carbon projects.

Data on carbon project forwards is typically not publicly available, as they are bespoke contracts between buyers and sellers (i.e., project developers). Through speaking with project developers, we typically see that forward prices are discounted, reflecting the project risks buyers absorb by providing upfront financing. Meanwhile, the nascency of the spot carbon market could give rise to pricing volatility due to temporary market shocks.

We expect that forward contracts will become increasingly popular as supply becomes limited and buyers demand more visibility and transparency throughout the entire carbon project development cycle. Most importantly, they provide project developers with critical market signals and access to private finance as they develop long-term carbon reduction and removal projects with high costs now for credit delivery and payments in the future.

But…is any of this pricing fair?

Our standard macroeconomic models often fail to explain the many unintended costs and benefits of a transaction on third parties. Just as the co-benefits of carbon credit projects are hard to measure, it is equally hard to determine the fair price to pay for an activity that reduces or removes one metric tonne of CO2. One way to understand this concept of “fair pricing” is through the social cost of carbon, which is the theoretical estimate of the cost of damage to society done by each additional tonne of carbon emissions (or, on the flip side, the benefit of reducing or removing one metric tonne of CO2).

The Obama and Biden administrations have led rigorous exercises into determining the social cost of carbon to guide policy decisions, setting it between US$ 43–51 per metric tonne of CO2e, while the EPA has proposed raising it to US$ 190. These figures are notably higher than the prices we see in the voluntary carbon market, which begs the question: are the current prices in the voluntary market sustainable and fair, given the social benefits it could bring through reducing or removing carbon emissions?

From these perspectives, it is clear that carbon credits on the VCM are currently trading at steep discounts due to a lack of standardization and institutional gaps, coupled with a lack of consensus around the true cost of emitting carbon. There is also a real need for varied pricing to differentiate between crediting methodologies and project specifics.Recognizing this, NetaCarbon’s primary focus is to build systematic approaches and methodologies to support suppliers in gaining easier access to the VCM. We can help them by streamlining regulation navigation, the verification and quality certification process, and project management. In doing so, we aim to close the supply gap of carbon projects and reduce the overall climate cost to our planet and globally underserved communities. If you are interested in developing a carbon project, please reach out to us!

We would like to thank Amrita Roy for her contribution to this blog post and Rehan Mirza for editorial support. For this blog post, we drew upon data from the World Bank, Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, Trove Research, and S&P Global Platts.

The voluntary carbon market (VCM), as with any marketplace, has buyers and sellers who agree on a common price for credits. It is designed for the private sector where corporates (the buyer) can purchase carbon credits either directly from project developers (the seller) or indirectly on marketplace platforms. This can help them reduce their net emissions and even potentially remove CO2 from the atmosphere, outside of the purview of their own supply chains. This is in contrast to compliance carbon markets – typically a cap-and-trade system where government entities mandate and regulate carbon trading activities – which facilitate trading on carbon emission allowance between firms.

Since 2000, 1,800 million metric tonnes of carbon credits have been issued across the four main registries (Verra, Gold Standard, CAR, ACR), as of Q1 2023. In 2022 alone, 146 million metric tonnes of CO2 were retired on the VCM, according to data from the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project. However, there is significant variation in pricing based on project methodology as seen through World Bank’s tracking, based on data from S&P Global:

Exhibit 1: Pricing of carbon credits by project type, according to pricing data tracked by S&P Global.

As such, much of carbon credit pricing remains opaque and difficult to grasp, especially for newcomers to the market – why is one tonne of CO2 valued differently across projects?

Some commentators take a “commodity” approach, arguing that there should be a uniform price across all carbon credits, just like most other traded commodities. However, similar to many climate practitioners, we see the necessity of varied carbon credit prices. In this blog post, we demystify why carbon prices vary due to three major factors, which illustrate why we still believe they should continue to vary.

Factor 1: Project Types & Methodologies

The number one determining factor for carbon credit pricing is the project type – whether it is a carbon removal or reduction/avoidance credit, and whether it is a nature-based or engineered removal credit. The project type has an implication on the cost of project development and any other potential revenue streams for the project outside of the financing received from carbon credits. As a rule of thumb, removal credits, which often rely on engineering interventions, tend to be more expensive than reduction credits due to higher technological costs and limited alternate revenue streams.

Trove Research, a research firm specializing in VCM-related data, explains the cost ranges of the most common types of projects and how they are predicted to evolve, which we summarized in the chart below. Note that a project developer would need to factor in additional costs related to verifying and issuing a carbon project and their margin to determine the ultimate selling price of each unit of carbon credit.

Exhibit 2: Cost ranges by major categories of carbon credits.

Their research demonstrates that project development costs can vary considerably, which in turn would result in a divergence in pricing across carbon projects. Based on these supply-side constraints, we cannot assume a blanket price simply because each project technically represents one unit of carbon dioxide reduction or removal.

Their work also shows that the cost of carbon removal technologies will fall with time due to ongoing innovation spurred across countries through compliance mandates and/or market incentives, like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the United States. The resulting economies of scale and learning effects will further create new technological solutions not yet viable today. Nevertheless, the average price of carbon credits is still expected to increase due to increasing pressure on productive land use, global and local economic growth, and improvements in credit quality and measurement technology which will improve the quality of carbon credits available on the VCM.

Factor 2: Quality and Co-Benefits

The quality of a carbon credit is another key factor determining its market price. A high-quality carbon credit adheres to ICVCM's ten core principles, as we discussed in an earlier blog post. Strong supporting evidence on additionality, permanence, and absence of leakage legitimizes and justifies a higher credit price. Conversely, the uncertainty on credit quality alone could tumble prices. REDD+ projects, which became the center of controversy due to suspected over-crediting claims, have seen their value halved from that of last year.

Associating strong co-benefits with the project also helps boost credit prices. Credits that demonstrate co-benefits like improving livelihoods, creating local jobs, and empowering women, taking on a more comprehensive understanding of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, have historically received 30.4% higher market prices.

However, co-benefits are much harder to quantify than the costs of a carbon credit project as they are either intangible or non-monetary (like improved community health). Moreover, available forms of measurement currently lack global metric standardization and disclosure principles.

But there’s hope! We are already seeing rapid development of new technology for robust verification, and quantification mechanisms that take all stakeholders into account and will help instill buyer confidence in the VCM. This is a testament to the increasing diversity of people coming together to fight climate change.

Consequently, project developers should strive to incorporate and quantify co-benefits toward local communities into their projects, ideally going above and beyond what is required by the verifiers. Our experience is that the better a project can quantify and display its co-benefits (with transparency and proofs), the more attractive the project will be to buyers, boosting the transaction prices higher than projects that display limited co-benefits.

Factor 3: Spot Pricing vs. Forward Contracts

A buyer can either pay a spot price (i.e., a price for immediate purchase and delivery of carbon credits from active projects) or commit to a forward contract, which locks in an agreed-upon price for delivery of the carbon credit at a future date. By locking in a fixed future price, forwards provide buyers with a financial instrument to reduce their risk exposure given fluctuating market prices; in turn, they provide project developers with pre-financing funds to implement the carbon projects.

Data on carbon project forwards is typically not publicly available, as they are bespoke contracts between buyers and sellers (i.e., project developers). Through speaking with project developers, we typically see that forward prices are discounted, reflecting the project risks buyers absorb by providing upfront financing. Meanwhile, the nascency of the spot carbon market could give rise to pricing volatility due to temporary market shocks.

We expect that forward contracts will become increasingly popular as supply becomes limited and buyers demand more visibility and transparency throughout the entire carbon project development cycle. Most importantly, they provide project developers with critical market signals and access to private finance as they develop long-term carbon reduction and removal projects with high costs now for credit delivery and payments in the future.

But…is any of this pricing fair?

Our standard macroeconomic models often fail to explain the many unintended costs and benefits of a transaction on third parties. Just as the co-benefits of carbon credit projects are hard to measure, it is equally hard to determine the fair price to pay for an activity that reduces or removes one metric tonne of CO2. One way to understand this concept of “fair pricing” is through the social cost of carbon, which is the theoretical estimate of the cost of damage to society done by each additional tonne of carbon emissions (or, on the flip side, the benefit of reducing or removing one metric tonne of CO2).

The Obama and Biden administrations have led rigorous exercises into determining the social cost of carbon to guide policy decisions, setting it between US$ 43–51 per metric tonne of CO2e, while the EPA has proposed raising it to US$ 190. These figures are notably higher than the prices we see in the voluntary carbon market, which begs the question: are the current prices in the voluntary market sustainable and fair, given the social benefits it could bring through reducing or removing carbon emissions?

From these perspectives, it is clear that carbon credits on the VCM are currently trading at steep discounts due to a lack of standardization and institutional gaps, coupled with a lack of consensus around the true cost of emitting carbon. There is also a real need for varied pricing to differentiate between crediting methodologies and project specifics.Recognizing this, NetaCarbon’s primary focus is to build systematic approaches and methodologies to support suppliers in gaining easier access to the VCM. We can help them by streamlining regulation navigation, the verification and quality certification process, and project management. In doing so, we aim to close the supply gap of carbon projects and reduce the overall climate cost to our planet and globally underserved communities. If you are interested in developing a carbon project, please reach out to us!

We would like to thank Amrita Roy for her contribution to this blog post and Rehan Mirza for editorial support. For this blog post, we drew upon data from the World Bank, Berkeley Carbon Trading Project, Trove Research, and S&P Global Platts.

Since you made it this far, why not sign up for our newsletter?

Since you made it this far, why not sign up for our newsletter?

See what's possible

Build your sustainable brand presence while investing in the planet together.

See what's possible

Build your sustainable brand presence while investing in the planet together.

See what's possible

Build your sustainable brand presence while investing in the planet together.

See what's possible

Build your sustainable brand presence while investing in the planet together.

Stay up to date

2024 NetaCarbon. All rights reserved.

Stay up to date

2024 NetaCarbon. All rights reserved.

Stay up to date

2024 NetaCarbon. All rights reserved.

Stay up to date

2024 NetaCarbon. All rights reserved.